Brigham’s Growth

Spurred by private business and a more stable tax base, Brigham City entered a relatively prosperous period in the 1880s and 1890s, evidenced by a growth in both housing and public improvements. Some of those improvements were based on technology like telephones, electricity, and indoor plumbing became available; others simply on access to cash sources and products not readily available during the Co-op period.

Although Brigham City was founded in 1867, no written records of City Council business prior to 1875 have been located. At first, the Council met on a quarterly basis or when needed, then monthly, and were meeting bi-monthly by 1894. The first recorder included the Courthouse as the venue, but later recorders do not list a meeting place. Early council meetings began at 10 a.m., adjourned for lunch, then met again at 2 p.m. In the late 1880s, evening sessions replaced those previously held in the afternoon.

Roads and Streets

When Brigham City was platted in the mid-1850s, the streets were given names, not the traditional numbered system of most Mormon towns. As additional surveys extended the city’s boundaries far beyond Plat A, this practice was continued up until 1900.

On a survey by Jesse W. Fox in 1868, streets centered at Main & Forest (East Forest was Locust) streets to the north were North Street, North Wall, Columbia (probably the reason the Fourth Ward school was named Columbia), Cambridge, Chestnut, Vine and Pine (700 North). South of the courthouse, the streets were South, South Wall, Tabernacle, James, Washington, Jefferson, and Liberty (700 South). West of Main was Young, Farming, West, West Wall, Locust, and Cherry (600 West). East of Main was Pleasant, Box Elder, High, East Wall, and Walnut (500 East).1Map of Brigham City, compiled from original surveys of Brigham City and research from LDS Church historical data by Veara S. Fife and Chloe N. Peterson, 1976, on survey by Jess W. Fox and certified by him on 12 Feb. 1868.

The intersection of Main and Forest, where the Courthouse is located, was always the center of the city, with Forest Street jogging north to accommodate the Public Square. Although its eastern portion was originally called Locust Street, the Bird’s-Eye View of Brigham City by E. S. Glover in 1875 shows its name as Forest Street.2E. S. Glover, Bird’s-eye view of Brigham City and Great Salt Lake, Utah Territory, 1875, (Cincinnati: Strobridge Co. Lith., 1875). Perhaps this was to avoid confusion with the other Locust Street.

Streets were often the topic of discussion in City Council meetings, with bills submitted by various residents for road and bridge work. Most streets were dirt, although some were graveled in later years. Horse-drawn water trucks were employed to sprinkle streets to keep dust down. In 1884, a rock bridge replaced the wooden bridge crossing Box Elder Creek between 400 and 500 North on Main Street. Wagon bridges and footbridges crossed the creek and irrigation ditches in other locations. Street work often occurred in conjunction with work on watercourses, which generally were located beside roadways.

Main and Forest streets were the most important, especially after the arrival of the railroad. Most important visitors, including Brigham Young, used the railroad as their primary form of intercity travel, so West Forest became the showcase entry into town. In 1878, City Council purchased shade trees to be planted on the “wide street or road leading from the courthouse to the UNRR station” and petitioned the county court for an appropriation to help defray costs of these improvements.3Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: 1878).

Water System

Controlling water resources began early in Brigham City, with surveys of the city including not only streets, but also ditches to distribute water to the platted areas. Box Elder Creek water was used to power sawmills at the mouth of the canyon, and was channeled into millraces for the grist mill, as well as the Co-op woolen mill and planing mill.

Open wells, some of them fitted with hand pumps and others with the familiar “bucket-and-rope system,” were located in various areas of town. One of the oldest is still visible (2013) on former Reeder Family property at the corner of 700 West and 200 North. Those not fortunate enough to have a well depended on the open ditches as their water source.

Some of the first City Council minutes in 1875 record action to raise a water tax to increase the supply of water for irrigation on city lands, one of the first mentions of taxes. Watermaster Jeppa Jeppsen was allotted funds to repair and improve ditches, with $1,000 set aside to defray expenses incurred by construction of a canal along the creek to increase the supply of water for the city.4Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: Sept. 18, 1875).

In 1879, the council authorized the Watermaster “to cause some work to be done in the ‘little valley’ near Mantua to increase the water supply of the city.” In 1881, council minutes show a new “watercourse” to the southeast part of the city. That same year, it was decided that certain lots without access to water were of no use, and could be exchanged for another lot within the city or the sale price returned. The problem with open ditches was that they had many uses, not just culinary and irrigation. The Brigham Bugler often editorialized about their unsanitary conditions. Refuse was tossed into them, domestic animals were common on city streets, and many a family outhouse was located beside the flowing canals.

The topic of discussion at the City Council meeting on September 6, 1881, was dominantly about water: “the question of having waterworks in the city, which of late agitated among the citizenry, was informally discussed.”5 Minutes, Sept. 6, 1881.

One idea brought to City Council on July 15, 1891, by Mr. P. F. Madison was that the city obtain water for culinary purposes “through the medium of wells sank (sic) at a depth suitable to obtain flow enough to place a 3 or 4 inch pipe” and suggested that the city experiment with this, using Box Elder Creek to power pumps. A committee was appointed to look into the idea.6Minutes, July 25, 1891.

The committee reported back on August 29, that the wells would have insufficient flow, and it would be cheaper and more profitable to obtain water from the main creek somewhere near the mouth of the canyon “to be conducted to the city through a 3-6 or 8 inch pipe at a cost of about $15,000 . . .”7Minutes, August 29, 1891.

It was not until the term of Mayor Joseph M. Jenson, 1891-1893, that Brigham City developed a city water system. He saw the need to clean up waste from city streets and to install a sanitary water and sewage system. The City Council passed a resolution favoring a water system and providing for a bond to finance it. Although most citizens approved, some did not:

A few citizens, who when organized called themselves the Safety Society, were bitterly opposed to the movement. They brought injunction proceedings in the First District Court of Ogden to enjoin the council from bonding the city. They, however, lost their case.8Lydia Walker Forsgren, ed., “History of Box Elder County”, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 264-265.

A bond was issued for $24,000 to cover the project, which included a reservoir with a 160,000-gallon capacity located on Northeast Hill, which was later named Reservoir Hill, east of the Brigham City Cemetery. Water was supplied to the city through a network of eight-inch water mains. The project was completed and water turned into the pipes on July 9, 1892. The new system was well-received by the public, with more than 120 signed up as users within two months. At the end of six months, the water system was a paying concern.

The Jenson home was one of the first to have plumbing. Water was piped from the cellar to the second-floor bathroom. According to family tradition, some members of the household were reluctant to have an inside toilet because of the potential odor permeating the home. As a compromise, Jenson installed a flush toilet on the second floor away from the living areas on the main floor.”9Kathleen Bradford, Mayors of Brigham City 1867 to 2000, (Brigham City: Brigham City Corporation, 2000), 21.

A water system required employees. Minutes during the term of Mayor John D. Peters, 1893-1895, note salaries of $25 per month for Lorenzo Pett, City Watermaster, and $200 per year for J. P. Olsen, Superintendent of Waterworks. Peters also arranged for irrigation water and a sprinkling wagon for watering lawns during the summer months and hired Andrew Jensen to maintain the city waste-water ditch for $10 for the summer season.10Bradford, 25. Additional water sources were brought into the system during the term of Mayor John F. Erdmann, 1893-1900, with the approval of a canal to lead water from West Devil’s Gate and Bird Springs to the city’s water system.11Bradford, 37.

As the twentieth century began, a majority of Brigham City households had running water piped into their kitchens, although outhouses were still common in the community. Demand for water, due both to greater usage and a growing population, would call for higher capacity systems in the twentieth century.

Law Enforcement

Local government and the LDS Church were one and the same in Brigham City’s earliest pioneer days. The first record of official law enforcement came with the creation of Box Elder County in January 1856. Among those appointed as county government officials were Joseph Grover, Sheriff, and Eli H. Peirce, Justice of the Peace.

Law enforcement remained within county jurisdiction until Brigham City was incorporated in 1867, at which time John D. Burt was elected as Marshal. He was reelected in March 1875, and continued in office until Chester C. Loveland was elected and/or appointed in March 1877.12Dane Johnson, History of the Brigham City Police Department, unpublished manuscript, circa 1990, 2. (Johnson lists Loveland as being elected on March 5 but City Council minutes of March 24, 1875, refer to it as an appointment, perhaps an affirmation of election. Two-year terms would indicate an election process. Brigham City Council adopted an ordinance entitled “Crimes and Punishments” on December 18, 1875, but no copy of that document is on file. In 1876, a committee was appointed to draw up a report on police regulations, and discussion was held on “running about of dogs.”

On March 24, 1877, former Mayor Chester C. Loveland was appointed to serve as Marshal and Jailer, Ephraim Wight as Captain of Police, and Alex Baird as Sexton.13Minutes, March 24, 1877. Loveland had already been serving in law enforcement since at this same meeting he submitted bills for boarding two local prisoners. These individuals were both pardoned and released in April, with minutes concerning one prisoner stating he was “a young boy somewhat deficient in mental facilities and now feels penitent.”14Minutes, April 13, 1877.

A significant change took place in the City Council meeting of November 1, 1877. Wight was evidently a longtime police officer, as well, since when he tendered his resignation of Captain of Police on that date, he was issued a note of thanks for “efficient services for many years as chief of police in this city.” An ordinance was immediately passed to “connect” the office of Captain of Police with the office of Marshal, after which Loveland resigned from the City Council and received a vote of thanks.

The Marshal was then authorized to raise a force of policemen as (special) from all the able-bodied men from 16 to 60 years of age to perform duties when requested, to guard and protect the interests of this city.15Minutes, Nov. 1, 1877.

Marshal Loveland submitted regular bills for police services during 1878, which included overseeing fire protection. When the city council created an official Fire Department and appointed a Fire Chief on December 28, 1878, those duties were removed with the adoption of a motion stating: “in case of outbreak of fire, CC Loveland is released from further responsibilities and duties related to the Fire Department.”16Minutes, Dec. 18, 1878.

In early 1879, Jeppa Jeppsen was appointed a “general policeman” and building inspector “to guard the public interest of the city.” His salary as assessor, collector, and sexton was increased in light of his new duties.17Minutes, April 14, 1879./mfn] This was not unusual, as these early marshals and/or policemen usually had at least one other job with the city.

Occasionally, the council and mayor would order the marshal to take care of specific problems. He would be ordered to stop the juveniles from writing on the walls of the tabernacle or to enforce the ordinance against unnecessary businesses remaining open on Sunday.17Lydia Walker Forsgren, ed., History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 1.

That summer Loveland submitted a bill for boarding and locking up 54 tramps in 1878 and furnishing meals to them, as well as boarding a local prisoner under sentence, and boarding tramps from March through May — 14 in number. His report on a trial for “lewd and lascivious conduct” included fees for Deputy Rais Cahoon, H. Stender, and J. Jeppesen for witness fees.18Minutes,June 3, 1879. Again in December, he submitted a bill for police service, including boarding transients and paupers, which seemed to be the primary police duty.

At that same meeting, the Council discussed the necessity of having a few policemen “always on hand to see that good order may prevail in the city.” The following persons were then appointed policemen: William Pulsipher, David Lindsay, George Parsons, George Nichols, Peter Johnson, John Johnson, James Nielsen, and Christian Olsen. It was ordered that in case of conviction for offenses in the alderman’s court, that “the officer making the arrest in cases resulting in the conviction of the parties shall be entitled to one half of the amount of the fines. . .”19Minutes, Dec. 2, 1879. Law enforcement continued as usual in 1880, with Loveland and Jeppesen submitting bills for police services. There is no reason stated for a particular action taken, stressing that licenses for “theatrical performances, balls and exhibitions be strictly complied with” which it thought would “help much to prevent small gatherings of parties with immoral proclivities.”20Minutes, Dec. 7, 1880. Neither is there an explanation for Loveland billing for extra time “during quarantine” in 1882 although it coincides with a bill from Nurse Kaiser for “work and nursing in the pest house.” On occasion, a bill would be submitted to pay one of the policemen for services, but they do not seem to have been called upon very often.

Loveland was reelected marshal three times, until David Rees was chosen for the position in March 1885. During part of his term, Rees also doubled as watermaster, and served as marshal until he was replaced by Heber C. Boden, who was elected in March 1891. During this period there were other persons serving as policemen, with Loveland submitting a bill for an arrest in 1891.21Dane Johnson, History of the Brigham City Police Department, unpublished manuscript, circa 1990, 2. Alex Baird was employed as night watchman, as well as city lamplighter.

During Boden’s term, he asked the Council to clarify whether he should receive remuneration for arrests separate from his salary, and was told that his salary should cover arrests. Boden only served one term, with David Rees reelected as Marshal in January 1894. Rees served one term before being replaced by Isaac A. Jensen, who served from 1896 to 1899.22Johnson, 2.

Baird remained as night watchman, and his duties must have included being night jailer. In December, 1895, he asked the City Council that a few blankets be provided for tramps and persons brought into the City Jail. 23Kathleen Bradford, Mayors of Brigham City 1867 to 2000, (Brigham City: Brigham City Corporation, 2000), 29. In addition, bunks were installed in the jail. The location or size of this jail is unknown, unless it referred to the room(s) in the county jail set aside for the city to house tramps, drunks, and prisoners.24Olive H. Kotter, Through the Years, (Brigham City: 1953), 13.

A small granite block building with hand-hammered crossed bars on its windows located east and south of the Courthouse was an early county jail. This is probably the jail referred to in the following:

During the latter part of the 90s the city had a constant weather report. Alex Baird hung different colors of flags on top of the county jail, erected near the courthouse in 1871, so they could be seen all over town. The position he hung them in declared to the citizens the kind of weather they could expect that day.25Kotter, 12.

In 1896, the County Court granted the city use of the brick portion of the county jail for the “tramp element.” It was decided that prisoners housed in the jail who did no work would receive only two meals a day. Those willing to work got three.26Kotter, 33. In 1897, the Marshal asked for and received help in meeting tramps at the depot “as the town was full of tramps.” The night watchman was assigned to help with this problem.27Kotter, 34.

A Bugler story reported in 1898 that an attorney had stated there was not “as vile and filthy a place in the whole world as the Boxelder (sic) county jail.” At this “a Box Elder officer, who is supposed to personally look after this palace, took exception to this mild charge.” A reporter agreed to accompany him on “an inspection tour of this delightful round-up for tramps, hobos and evildoers in general.” He reported, “The interior of the jail has lately been whitewashed (excepting for its apparent lack of spring house cleaning) the place is not so bad — for a jail” and urged an apology to Sheriff Davis.28Brigham Bugler, (Brigham City: May 21, 1898), 1.

Usual law enforcement duties were assigned to the Marshal up through the turn of the century, including orders that no cattle shall be allowed to run at large on streets, or that minors be kept out of the Temperance Hall.

Electric Power

Brigham City residents, like those across the nation, were excited over Edison’s invention of a practical electric light bulb and eagerly read accounts of city streets and private homes being lighted by this clean and odorless power. Salt Lake City and Ogden had electric light back as far as 1880, and steam-generated electricity began service in Provo in 1890.29Reed A. Olsen, Hydro-Electric Power in Brigham City: Its Growth and Development, Master’s Thesis, (Logan: Utah State University, 1970), 3. At this time, the local streets were still lighted by 12 coal oil lamps, first proposed in December 1882 by Councilman O. W. Stohl, who suggested “erecting a few lamps to be placed on some of the principal streets of the city.”30Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: Dec. 5, 1882). This was soon implemented. Nightwatchman Alexander Baird used a ladder to reach the lamps as he filled the lamps with oil, trimmed the wicks, and washed the globes on a regular basis. Nightly he lit them:

Rena Baird Hopkins remembered that when she was a child her brothers, Phil and John, often went with their father, Alex, who was a night watchman, to light the lamps. She recalled that he used a torch which he held high in order to reach the wicks. At day break he made the rounds and extinguished the flames in the lamps.31Louie Squires, Through the Years, Brigham City, Utah, p 25.

Natural gas had been looked to as a likely power source for Brigham City, touted by the first edition of the Brigham Bugler in 1890:

. . . inexhaustible flows have been struck on the border of our town. They are profitably utilized for burning great kilns of lime. But a few short years will escape, it is said, before our city will be illuminated hereby and our victuals cooked by the aid of this clean, almost inexpensive, fuel.32Brigham Bugler, (Brigham City: June 14, 1890).

However, farsighted local builders were taking no chances, and included the possibility of electric power along with gas pipes into business buildings and homes they constructed during this period of rapid growth. It was evident by 1891 that the populace preferred the idea of electric lighting, so city fathers began meeting with speculators and government officials from other communities which had electric power systems.

On July 25, 1891, City Council was addressed by Mr. A. Moulton, agent for Thompson Houston Electric Company of Chicago, “to erect a plant to light our city at a cost of $6,000, providing the city corporation bear one-half the expense ($3,000) and that the citizens purchase the balance.”Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: July 25, 1891). Councilors discussed this, with the idea that it was an issue that should be put to the residents, and Moulton’s proposal was not again noted in minutes.

City-owned power was considered from the very first, with City Councilor A. E. Snow suggesting on August 29, 1891, that a profitable plant could be set in motion for $6,000. He proposed that the city “appropriate $2,000 to purchase an electric light plant, providing a company could be formed to forward the other $4,000.” His fellow City Councilors voiced the concern that they should “not act hastily” and the issue merited more time.33Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: August 29, 1891).

Discussion continued and various options were considered, with the Brigham Bugler making reference to a printed circular urging the city to spend $50,000 within a year to bring in water, electric light, and fire protection, of which $18,000 would be set aside for an electric system.34Brigham Bugler, (Brigham City: February 21, 1891).

In early November 1891, local businessmen Oliver G. Snow and L. T. Peirce were granted a charter to construct and operate an electrical plant. A four-month completion date was set when the charter was granted. By the end of November, enough investors had been recruited. This was the beginning of the Brigham City Electric Light Company with F. C. Priestly as president; Herbert Moore, vice president; O. G. Snow, treasurer; Samuel Luke, secretary. Other major stockholders were Mrs. M. W. Dunn, L. T. Peirce, C.J. Rohwer, and N. P. Andersen. The franchise of the company extended for a 50-year period.35Reed A. Olsen, Hydro-Electric Power in Brigham City: Its Growth and Development, Master’s Thesis, (Logan: Utah State University, 1970), 4-5.

Since the old Co-op woolen mill on 500 East was vacant and already fitted for water power, the company planned to locate its plant in the building. Priestly traveled to Pueblo, Colorado, to purchase a used electrical plant. While he was out of town, poles and wire were put up in Brigham City. The first lines extended from the power plant on 500 East to Forest Street and west to 400 West, along Main Street from 200 North to 200 South, and along 100 West and 100 East. It included 30 street lamps, replacing the city’s 12 coal-oil street lamps, which had to be filled, lighted, and extinguished manually. There were two lights per block going lengthwise and one light width-wise.36Ibid., 5-6.

February 11, 1892, was a big night in Brigham City. Residents cheered as the first electrical current went through the wires at 9:30 p.m. and lamps illuminated the streets for a few minutes. Despite the fact that electric service was interrupted for four days to correct belt slippage due to the high-speed generator and to regulate the flow of water, residents were enthusiastic over the prospect of home and business lighting. The first lights illuminated only the streets and business buildings, but within a month private homes were using electric power. The homes of John Crawford, Thomas Blackburn, Heber Boden, and Clem Horsley were the first to have electric lighting.37Brigham Bugler, (Brigham City: May 28, 1892).

This power system had one major drawback: it was direct current, which meant the entire city was on one electrical circuit. If that circuit broke, all the lights went out. At the time, this was not seen as a major problem. Although direct current could only be used for lighting, that was viewed as electricity’s major purpose. It did not handicap the sale of power. Most businesses had been wired as the system was being put up, and lights were being installed in homes at a rapid rate by mid-March.38Reed A. Olsen, Hydro-Electric Power in Brigham City: Its Growth and Development, Master’s Thesis, (Logan: Utah State University, 1970), 7. More problematic was the inconsistent water flow of Box Elder Creek. Coupled with an announcement that the woolen factory would resume operations under new ownership, the power company decided in May 1892 to purchase a coal-powered 40-horsepower engine and relocate the power plant to a new building south of the railroad depot. An agreement was made with Union Pacific Railroad to build a spur track to deliver coal in return for free lighting at the depot and railroad yard.39Brigham Bugler, (Brigham City: May 28, 1892).

A very bright and steady light was produced by the new machinery. During a demonstration, Samuel Luke, company secretary, enthusiastically described the facilities as follows: “With the rapidity of lightning, it runs as smooth and noiseless as a cat stealing onto a mouse. The friction of the engine seems to have been reduced to a minimum.”40Ibid., (Brigham City: July 23, 1892).

Although the new plant was successful in the consistent quality of electric service, it was considerably more expensive than water power and the company was not breaking even financially. With profits down, acting managers Priestly and Luke (residents of a neighboring city) sold their holdings in the company to local residents, at which time the Brigham City Electric Light Company became a local corporation in every sense of the word.41Reed A. Olsen, Hydro-Electric Power in Brigham City: Its Growth and Development, Master’s Thesis, (Logan: Utah State University, 1970), 7.

Within six months, February 1893, the company officers decided to return to “free” water power and construct a new plant in the mouth of Box Elder Canyon. During this period, two new members of the corporation, prominent businessmen C. W. Knudson and J. Y. Rich, assumed leadership of the company.42Ibid., 10.

A rock powerhouse, approximately 20 x 30 with 28 inch thick walls, was built about 2,000 feet east of the present city-owned powerhouse. Water was diverted through an open ditch to the water wheel which was connected to the generator, and the dynamo purchased by Priestly was moved once again. Steady electric power served local subscribers well.

During the first year of electric light in Brigham City, many changes took place — changes which gave a great amount of protection as well as economic benefits. No longer were the people in constant danger of the oil lamps causing fires. Better lighting of the streets gave more protection to those people who were on the streets after dark. Lights were placed in the post office to protect the patrons going there at night time.

The financial gains can be illustrated by the financial reports of Brigham City. The following entries were made for the year ending March 1, 1891: ‘Oil for lighting street lamps $135.10, night watchmen and the lighting of the street lamps $490. For the year ending January 1, 1894, an entry was made that it had cost the city $511.45 to light the city streets. Since a greater number of lights were used with the new system, this indicates the financial savings was considerable. In 1891, the city had twelve old oil lamps, whereas in 1892, it had thirty electric lights.43Ibid., 10.

With the new power plant in full operation and new management by trusted local business leaders in place, it was expected that the Brigham City Electric Light Company would develop into a sound investment for its stockholders. However, the power company’s initial success was also its downfall. Electricity was convenient, clean, and its uses quickly expanded from mere lighting. By the turn of the century, local residents were demanding more electric power than the company facilities would provide, both due to increased population and to heavier usage. People also wanted lower rates comparable to neighboring communities, as well as electric power for home appliances and well pumps for irrigation.44Ibid., 11. The Brigham City Council stepped in with a request for improvement in the power system, beginning a whole new phase of negotiation and “power plays” between factions as the 1900s dawned.

Telephone

Although it had less impact at the time, even before Brigham City had a newspaper or electric power, it had at least one telephone. Rocky Mountain Bell Telephone Company was given permission to erect poles and run wires in Brigham City on December 3, 1889.45Lydia Walker Forsgren, ed., History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 37.

Telephones were considered more of a curiosity than a necessity at that time. It was not until approximately 1895 that records show a public toll telephone being installed at the Charles Davis rooming house, which was moved to Doctor Wade’s drugstore in 1897.46Sarah Yates, “It’s been 25 years since days of ‘number please,'” Box Elder Journal, (Brigham City: January 30, 1985).

It is interesting to note that the telephone was a factor in making Brigham City’s first public library possible. In December 1898 the Mutual Improvement Association completed a $1,000 library building in the town square. A cooperative arrangement was made with the telephone company for staffing. The one-room building was lined with cloth, not plaster, to save money. In one corner was the town telephone and in the center was a heating stove.47Ibid., 1. John E. Baird was called to serve as librarian, and was also appointed toll agent. The library exchanged free rent for the telephone station for Baird’s salary being paid by the company, a satisfactory arrangement since neither was considered a fulltime position. Shortly after settling into the job, Baird was called to serve an LDS mission. His sister, Rena Baird (Hopkins), took over in the same co-position in June 1899.48Ibid., 1.

In about 1900, when the company had about 25 subscribers, the first exchange was established in the Eddy Drug Store, with Wynn L. Eddy as manager and Rena Baird as operator. Telephones were gaining in popular use, moving from business use to home connections at the beginning 20th Century, entering a period when telephone service expanded to almost every household.

Fire Department

It was not until the disastrous fire that destroyed the Co-op woolen mill on December 21, 1877, that Brigham City government focused attention on the organization of a city fire department. Until that time, neighbors formed bucket brigades to transfer water from city canals to the location of a fire.

Although there was no community newspaper to report the incidence of fire, many family diaries note the burning of a home, outbuilding or business. City Council minutes of February 9, 1878, note:

“Councilor H. E. Jensen spoke upon the expediency of procuring fire engines and organizing companies to have charge of and regulate the use of the same and thought it proper to have an appropriation made to enable us to proceed in the matter, the same being necessary for the safety of the city in cases of conflagration.”49Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: February 9, 1878).

A committee of three — H. P. Jensen, E. A. Box, and A. Nichols — was appointed to consider protocol to proceed to organize and establish fire companies and produce the necessary implements.

Upon the committee’s recommendation, Brigham City’s first firefighting unit was created on April 16, 1878, when the City Council appointed Mayor Chester Loveland to organize a fire company. He accomplished that task by December 28, at which time Lars Mortensen was selected as chief, with Jeppa Jeppsen and James Pett as assistants.50Ibid., December 28. 1878.

Since there was no city water system at this time, firefighting was a difficult job. Water was pulled by a hand-operated pump from city irrigation canals. This early department functioned sporadically through the years, hampered by a lack of organization and equipment and finally succumbed.

Organization of a firefighting company parallels that of the city water system, which was turned on at a public ceremony on July 9, 1892, and had sufficient pressure to shoot water 20 feet over the height of a three-story building.51Sarah Yates, “Brigham Fire department marks 100 years of service,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: November 19, 1978), 1. By the end of July, water had been piped into the courthouse. Stores and homes were clamoring for water service, and the system was a paying concern within six months.

By the time the water system was assured, a city fire department had been established on a more formal basis. It was officially organized on June 2, 1892, with Heber C. Boden appointed as fire chief. Members of the department were John Funk, Lorenzo Petersen, Orson Hudson, Oliver Ingram, George W. Ingram, Alfred Olsen, W. H. Glover, W. C. Horsley, John Dick, C. E. Horsley, Charles Watkins, John P. Christensen, Fred C. Petersen, Thomas McMaster, Ernest P. Horsley, Wallace Boden, L. T. Pierce, Henry Steed, Isaac A. Jensen, Lorenzo W. Andersen, Fred Kelly, John H. Horsley, Lawrence Berg, James Christensen, and Peter N. Pierce.Ibid., 1, 8.

The firemen were unpaid volunteers. In fact, they were fined 50 cents for missing a fire or drill, and those failing to pay this fine were expelled from the department.52Kathleen Bradford, Mayors of Brigham City 1867 to 2000, (Brigham City: Brigham City Corporation, 2000), 29. They were granted the use of a room in the courthouse for meetings during non-business hours.

The volunteer group began looking for a room in which to meet and to establish a room for exercise. October 21, 1892, fire department minutes note that chairman P. N. Peirce had engaged the basement of the Armeda building, 24 South Main, for an athletic and reading room. It was equipped with items for boxing, a horizontal bar, Indian clubs, etc. It was to be open every afternoon Tuesday through Saturday, but not after 10 p.m.

A hook-and-ladder truck became the first priority of the new department since they were relying on the old department’s antiquated equipment. Chief H. L. Steed, elected in 1893, attended the World’s Fair in Chicago, and was asked to check on a “gong” as well as the costs of other equipment. On December 17, 1893, the city council agreed to assist in the purchase of a hand-pulled $400 hook-and-ladder truck equipped with buckets, axes, 500 feet of hose and two nozzles. The city appropriated $150, citizens pledged $50, and organizations planned benefit events. The department was still lacking $50, so the department raised money with a July 4 dance the following summer. That dance was only one of many social events held by the department during their early years, usually for equipment or benefits for department members leaving on missions. A surprise party honored Chief Steed upon his resignation, with Clem Horsley stepping in as chief.

Not everything went smoothly for the new department. In 1895 the “matter of card playing in the hose house” was referred to the town marshal.

Misbehavior wasn’t unknown among volunteers, either, with one fireman receiving a dishonorable discharge for “neglect of duty and failing to obey rules of the department” in 1898. Chief Lorenzo Peterson prohibited anyone except firemen from riding on the truck, and it was occasionally felt necessary to give a lecture on temperance.

But there was also progress. The newspaper had a campaign to raise funds for protective clothing, and the department purchased lanterns, speaking trumpets, badges and new hydrant wrenches.

There is no record of where the “hose house” was located, but pressure continued for a new fire station. In November 1896, minutes note that the “chief made a few remarks against paying $44 desired by A. E. Snow for rent of the Fire Station and favorable remarks concerning the erection of a building of our own.” They agreed to “strike while the iron was hot” and to present the matter to the city council. [,fn]Fire department minutes, (Brigham City: November 11, 1896).[/mfn] In May 1897 the city council turned over a new wooden structure to the fire department for them to furnish. A notation splashed across the page of the minute book notes: “Removed trucks to new quarters north of the courthouse, May 15, 1897.” The wood structure was the firehouse for the next few years as leadership passed to Joseph Packer in 1898, then to C. E. Horsley in 1898-1901.

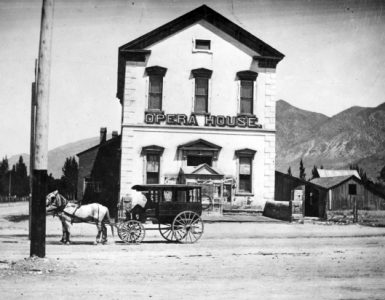

A fire log indicates the department was called out regularly. There were fires at the old Co-op building, Hunsaker Law Office, new Co-op building and the Opera House, but most fires were at private homes and outbuildings. Causes listed most frequently were sparks on the roof, small boys with matches, and “unknown.” Arson for profit was not unheard of, even in those days. A notation of a July 1896 fire in a lumber barn listed as its cause “too much insurance.” The most famous fire of the 1890s received the following report in the fire log: “February 9, 1896 — alarm at 1:45 p.m. in Box Elder tabernacle between Wall and Tabernacle streets on Main Street. Cause — defective heater; loss $25,000, no insurance.”

Modernization of the town also caused concern in the fire department as streams of water came in contact with electric lines and some men received severe shocks. A. Hillam and W. Taylor were appointed to visit the city council about wire dangers and action was suggested against the electric company.53Sarah Yates, “Brigham Fire department marks 100 years of service,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: November 19, 1978), 8.

Up until the turn of the century the fire department owned its own equipment, but they voted in 1901 to turn over to the city “all apparatus now and forever belonging to the department.” It was the dawn of a new era for the fire department.

City Cemetery

Although the Brigham City Cemetery was not officially surveyed into lots, blocks, and plats until 1880, the area was designated as a burial ground soon after the settlement of the city and has always been the local cemetery.

According to records in the Brigham City Cemetery Department, the first burial was made on October 12, 1853, for the remains of Mary Ellen Wight, born September 26, 1853, in Brigham City. This burial is located on the lot of Charles Wight, Jr.54Howard B. Kelly, History of Brigham City Cemetery, (Brigham City: February 15, 1964), 1. Howard Kelly, cemetery superintendent from 1955-1977, searched for that first grave for many years and asked people about it. One day, as a tree was being cut back, a sandstone marker several inches below the sod confirmed its location in the original northwest section. His enthusiasm at the discovery was shared by local monument maker Max Bott, who felt the tract ought to be marked more visibly. He made and donated a 12 x 16 inch granite marker.55Ibid., 1. The original sandstone marker revealed that the young couple, Charles and Sarah Ellen Loveless Wight, buried three more infant daughters: Sarah, in 1858; Anna in 1859 and Lucy in 1861.56Lori Hunsaker, “Memorial Day draws visitors to BC Cemetery, rich in heritage,” Box Elder News Journal, (Brigham City: May 22, 1996), 17.

According to Kelly, the second burial in the cemetery was also an infant, Margaret Caroline Davis, born July 1, 1854, died July 10, 1854, in Brigham City. No information is recorded for her parents or the location of this burial.

The cemetery policy book states there is a mass burial of railroad workers killed by cholera as they worked along the railroad through the county in 1869.57Editor’s note: This seems rather unlikely, as most railroad workers were buried fairly near where they died, and usually not in town cemeteries. Additionally, a search of newspapers from the time revealed cholera outbreaks at other times and places among railroad workers, but not in Utah in 1868 or 1869. There are two possible locations of that burial, according to sextons. One is the triangle just inside and to the left of the corner entrance at 300 East and 300 South, or an area in the southeast corner of the cemetery known as Potter’s Field. This particular Potter’s Field is so named because during the Depression, the city allowed burials for those who could not afford to buy a burial plot. The city will never sell burial rights in either location. Lori Hunsaker, “Memorial Day draws visitors to BC Cemetery, rich in heritage,” Box Elder News Journal, (Brigham City: May 22, 1996), 17.

During the pioneer period, relatives and friends of those who had lost a loved one prepared the grave by hand digging, and there was little information recorded on the location of burials unless the family placed a wooden or stone monument. A family’s ethnic heritage, economics, and the availability of resources determined forms of caring for the deceased. Wooden boxes constructed by hand from local timber were the most usual form until caskets became a commercial item in the latter part of the century. Some graves were prepared by laying of brick vaults; others were heavily braced with timber.58Howard B. Kelly, History of Brigham City Cemetery, (Brigham City: February 15, 1964), 4.

From 1853 to 1877 some burials were recorded properly as far as lot, block, and plats were concerned, but there was no definite pattern that could be followed. Despite its use since the time of earliest settlers and appearance on some maps, precise cemetery boundaries and sites were not on any official record.

On November 1, 1877, the City Council considered the “expediency of erecting a substantial fence” around the cemetery, and Councilor E. A. Box was appointed a committee of one to examine the dimensions of the burying grounds and make an estimate of the cost of materials and labor to build a fence. He was authorized to take with him “such men as he may select” to assist in forming such an estimate.59Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: November 1, 1877). That report was awhile coming, for it was May 5, 1880, before the subject next surfaced in City Council minutes, which noted: “The subject of location of the burying ground was then taken up, with an outline of the same having been sketched by surveyor Wright.”60Ibid., May 5, 1880. A special meeting was scheduled on May 15 for council members to meet at the graveyard to examine the plans.

On June 8, 1880, the City Council authorized a survey of the entire cemetery to be plotted into lots, blocks, and plats. Residents could buy cemetery lots for $1.25, $2.50, or $5, depending on size. During that summer, a contract was let to water trees, as well as to erect a “substantial” fence around the cemetery, with pickets 5-1/2 feet high.61Ibid., August 3, 1880. The first deed was issued on March 22, 1886. These were, and still are, permissive burial right deeds only, which means that the cemetery itself remains city property.62Howard B. Kelly, History of Brigham City Cemetery, (Brigham City: February 15, 1964), 3.

References to “location” related to establishing perimeters and those concerning the new fence indicate that the cemetery had “lately been extended” with the new survey. Approximately 15 acres, with adjustments allowed for streets bordering the cemetery, were included.

From that time on, personnel in charge of burials were able, to a certain degree, to record burials in the right locations on the individual lot owner’s property. Men in charge of the cemetery were paid a partial salary to supervise the location and digging of graves (still up to the family or friends), record burials, and to generally care for the cemetery. City records list the following persons who served as sexton (also known as cemeterians) during that period: Jeppa Jeppson, 1887-1891; Thomas Forest, 1891-93; John Forrest, 1893-1896; Brigham Jensen, 1897-1902.63Ibid., 3. (Kelly notes that Thomas Forrest was his great-grandfather, and John Forrest was his grandfather.)

In 1888, the city purchased a horse-drawn hearse for $355, appointing S. N. Lee as driver and caretaker of the coach and the horses which pulled it, at the same time authorizing the erection of a suitable shed in which to house the coach.64Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: October 19, 1888). The hearse was available, free of charge, to all citizens within the boundaries of the city. At the time of LDS President Lorenzo Snow’s funeral in 1901, his coffin was transported from the train depot in this hearse, drawn by four white horses, first to the Tabernacle for the services and then to the cemetery for burial.65Kathleen Bradford, Mayors of Brigham City 1867 to 2000, (Brigham City: Brigham City Corporation, 2000), 16.

Up until 1900, there was little organized effort at beautification, except by individual families who planted trees, bushes and flowers, placed monuments, or erected decorative fences or concrete coping around their plots. Each year, prior to Memorial Day, it was a common practice for families to come to the cemetery to clean up their individual lots. The City furnished men and teams to haul away the trash.

The sexton reported regularly to the City Council on the number of interments, as well as causes of death. Included were brain fever, dropsy, consumption, measles, typhoid, summer complaint, cholera, mountain fever, whooping cough, scarlet fever, diphtheria, Bright’s disease, pneumonia, bronchitis, appendicitis, pleurisy, erysipelas, hemorrhage, paralysis, fits, convulsions, heart disease, kidney disease, old age, and one case of cancer, as well as railroad and other accidents, and entries simply listed as “killed.” Infant mortality was high, with stillbirth, premature birth, teething, and croup listed as causes, and childbirth and childbed fever were not uncommon. Indians were occasionally interred, usually without a listed cause of death. In 1879 and also 1897, there were diphtheria epidemics — 16 children died of this dreaded disease in 1879 and 19 died of the same malady in 1897. Some families lost two and three children in a matter of a few days during these epidemics.66Howard B. Kelly, History of Brigham City Cemetery, (Brigham City: February 15, 1964), 3. Deaths from typhoid fever were also frequent, perhaps due to the city’s lack of a clean water system.

Brigham City’s history is reflected in the cemetery monuments: founders William Davis and George Hamson are buried there; as is its famous colonizer, Lorenzo Snow, who went on to become LDS Church President; along with Samuel Smith, postmaster, probate judge, and mayor; and a host of other individuals important to the city’s past.

Cemetery monuments, and the records that go with them, are a treasure trove for historians and genealogists. Where possible, the records not only indicate exact location of a grave but also contain names of the deceased person’s parents, spouse, date and place of birth, date and place of death, and date of burial.

Many of the monuments dating back to the cemetery beginnings are hand-carved, one-of-a-kind, priceless works of art. A good number of these are attributed to the employees of Box Elder Marble and Granite Works, which existed back as far as 1877. 1n 1892, its proprietor, John H. Bott, purchased the company, and continued the trade.

City Parks

Public space for city parks and buildings were set aside in Brigham City’s original plat, including the central square where the Courthouse and City Hall were built. Temporary willow boweries were erected for summer gatherings, including the one erected between 200 to 300 West on Forest Street where Brigham Young delivered his final speech.

John D. Rees, mayor from 1875-1878, began a project to plant trees along Forest Street from the city square to the train depot. During his first year in office, he donated the property now known as Rees Pioneer Park, west of 600 West and north of Forest Street, to the city.67Kathleen Bradford, Mayors of Brigham City 1867 to 2000, (Brigham City: Brigham City Corporation, 2000), 8. In May, 1890, City Council directed that the pond in the park be confined to the south with a substantial dam. They decided that the eight acres, including the pond, should be called Rees Park in honor of its donor.68Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: May 12, 1890). As near as can be determined, additional acreage was purchased at this time. City maps of the period show a race track located north and west of the park, east of the railroad tracks. Later the Daughters of Utah Pioneers requested the name be changed to Pioneer Park in remembrance of early settlers, and it has since been known as Rees Pioneer Park.

In April, 1882, the City Council purchased an area, later known as Reeder Grove, located at 700 North and 600 West. The city paid $600 to the Brigham City Mercantile and Manufacturing Association (Co-op) for the grove, through which the tree-lined Box Elder Creek flowed. It was available to local residents for picnics, church and family gatherings, simply by obtaining a permit from the city. The city sold the grove to the highest bidder, George B. Reeder, in May 1894.69Olive H. Kotter, Through the Years, (Brigham City: 1953), 12.

A small park was established on April 3, 1890, as the Council approved plans to “prepare ground and set out shade trees on a tract of land” on First (or Second) East near B.M. Young’s residence, and “put it in shape for a public park.” Two hours of irrigation water were set aside to “insure pleasant undergrowth” in the park.

The square across from the Tabernacle was designated as public ground, and early maps show it bordered by trees. There is record of it being used as a gathering spot and campground. As early as 1885, the city was approached with a petition to have the square “west of the new tabernacle deeded to School Trustees and successors for the purpose of erecting a suitable school house”70Brigham City Council minutes, (Brigham City: September 8, 1885). but the property remained vacant until 1900.

LOVE this website. Thank you so much for compiling all this terrific information about this fascinating town.