Outside events would soon cause disruption of normal life in all the northern settlements. The Utah War, in which no battles were actually fought, resulted in a mass dislocation of people called “The Move South.”

In the spring of 1857, President James Buchanan appointed a non-Mormon, Alfred Cumming, as governor of the Utah Territory, replacing Brigham Young, and dispatched troops to enforce the order. The Mormons prepared to defend themselves and their property, and Young declared martial law and issued an order on Sept. 15, 1857, forbidding the entry of U.S. troops into Utah. The order was disregarded, and throughout the winter sporadic raids were conducted by the Mormon militia against the encamped U.S. Army.1L.R. and A.W. Hafen, ed., The Utah Expedition, 1857-58, (1958).Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859, (Salt Lake City: 1960,1977).

In the face of this supposed threat, the Nauvoo Legion began enlisting men from Box Elder and Weber Counties into the Fourth Regiment. About one hundred men from Brigham City volunteered and were assigned to Company A of the 5th Battalion under the command of Samuel Smith.2Nielson, Vaughn, and Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, The History of Box Elder Stake: written in commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of Brigham Young’s setting in order a state for Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Box Elder Stake, 1977), 16. President Young announced in March 1858 that all settlements in northern Utah must be abandoned and prepared for burning if the US Army should arrive to take over. Settlers living north of Utah County abandoned their homes and moved southward, leaving only a few men in each town and settlement. Major Samuel Smith remained with a rearguard in Brigham City, where he assigned Willis H. Boothe to command the “minutemen” in preventing the Indians from burning the settlement, though they were instructed to do so themselves should hostile soldiers enter the valley.

One can imagine the feeling of the people as they left their homes and farms, but God was pleased to bless their lands and much grain and hay ripened unattended and their houses, which were broken into by curious Indians who strew things about were otherwise left intact. Most of the exiles from Brigham City located temporarily near Payson, Utah County, living in their wagons and dugouts, existing on the year’s supply of flour brought with them.3 Nielsen, 17.

A touching story written by Eva Dunn Snow, granddaughter of early pioneer Simeon A. Dunn, tells of her family’s move. Dunn’s wife, Harriett, gave birth to twins on December 31, 1857. The tiny girl died shortly after birth and two days later Harriett died, and both were buried in Brigham City. Ms. Snow adds:

A touching story written by Eva Dunn Snow, granddaughter of early pioneer Simeon A. Dunn, tells of her family’s move. Dunn’s wife, Harriett, gave birth to twins on December 31, 1857. The tiny girl died shortly after birth and two days later Harriett died, and both were buried in Brigham City. Ms. Snow adds:

Three months later, in April 1858, the call came for all Saints to leave their homes in northern Utah, and journey southward. Simeon Adams Dunn loaded a few provisions and household effects into his covered wagon, assisted his motherless children to their place in the wagon box, and cracking his long whip over the backs of his oxen, commenced his journey. He had also provided a wagon for his eldest daughter (Mary Dunn Ensign) and her three little girls and they traveled together. The husband and father of this little family, Martin Luther Ensign, at that time was serving as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (in England).

As they proceeded on their way, baby Henry became very ill. They camped on Kay’s Creek, (now Kaysville) and there they saw the life depart from their lovely three-months-old baby son and brother. The father made his little family as safe and comfortable as possible in this temporary camp, and with a sad and heavy heart slowly wended his way back to the lonely grave in the Brigham City Cemetery. Very near to it he dug a very small, new grave, and in it tenderly laid the remains of his baby boy.

He found the town empty, except for a few men who had remained behind, ready at a moment’s notice to touch a match to the homes and buildings if the enemy should enter the city. He went into his house, expecting to spend the night there, but it was so quiet and lonely it was more than he could endure, so he went to the stable, laid down by his faithful oxen, and spent the night near them. Early the next morning he was on his way to rejoin his family. He found them safe and well and they continued their journey as far south as Payson, where they made their camp and remained until the Saints were counseled by the Church leader, to return to their homes.4Kate B. Carter, Heart Throbs of the West, Vol. 10, (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneer), 259-260.

The Utah War ended without conflict. Negotiator Thomas Kane and Cumming came to the Mormon capital for negotiations in early April 1858. Brigham Young immediately surrendered the gubernatorial title and soon established a comfortable working relationship with his successor.

However, neither of the non-Mormons could encourage Young’s hope that the army might be persuaded to go away, nor could they give him convincing assurance that Johnston’s troops would come in peacefully. So the Move South continued.5Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859, (Salt Lake City: 1960,1977).Richard D. Poll, Quixotic Mediator: Thomas L. Kane and the Utah War, (1985). It wasn’t until July 1, that Orson F. Whitney recorded, “A peaceful settlement having been reached with the U.S. Army, most of the people returned to their deserted homes and resumed their accustomed labors.”6Nielson, Vaughn, and Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, The History of Box Elder Stake: written in commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of Brigham Young’s setting in order a state for Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Box Elder Stake, 1977), 17.

After the Move South

Residents picked up their lives where they had left off, continuing with a pattern of life that had evolved from the earliest days as pioneers had begun specializing in their talents and trades to create a well-rounded community. Families completed the journey home by late summer or fall. The men left behind to guard the settlement had been faithful to their neighbors in watering crops, and returning residents were glad to see most crops had thrived and ripened through the summer, as in the case of William Wrighton’s peaches.

Wrighton settled in Brigham City in the spring of 1855. On his yearly trip through Utah Territory that summer President Young encouraged people to plant fruit trees, both for the production of fruit and to beautify their property. That fall as Wrighton attended October Conference in Salt Lake City he saw peach stones being sold at one dollar per hundred. Taking his peach stones home, he put them where they would freeze during the winter, and then planted them in the spring. The next season he set the seedlings 16 feet apart on his lot on the southwest corner of First West and First South. After watering his orchard through May of 1858, Wrighton was ordered to join the Move South and arranged for a friend who remained to stand guard to irrigate the trees until his return in the fall, and came home in time to pick his first ripe peaches.7Lydia Walker Forsgren, History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 60. Editor’s note: It is highly likely the timeline of the story was shortened, as it is unlikely peaches grown from pits would produce fruit within two years (three years is the minimum time expected).

Wrighton settled in Brigham City in the spring of 1855. On his yearly trip through Utah Territory that summer President Young encouraged people to plant fruit trees, both for the production of fruit and to beautify their property. That fall as Wrighton attended October Conference in Salt Lake City he saw peach stones being sold at one dollar per hundred. Taking his peach stones home, he put them where they would freeze during the winter, and then planted them in the spring. The next season he set the seedlings 16 feet apart on his lot on the southwest corner of First West and First South. After watering his orchard through May of 1858, Wrighton was ordered to join the Move South and arranged for a friend who remained to stand guard to irrigate the trees until his return in the fall, and came home in time to pick his first ripe peaches.7Lydia Walker Forsgren, History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 60. Editor’s note: It is highly likely the timeline of the story was shortened, as it is unlikely peaches grown from pits would produce fruit within two years (three years is the minimum time expected).

Most industries began in homes, and then sometimes moved to a built-on room or an outbuilding, before establishing a separate entity located in the emerging business district.

Starting with the first settlers, hospitality to travelers was important, whether they were visiting church officials, emigrant parties, or the growing numbers of freighters moving supplies to various locations. Local religious leaders were usually responsible for housing church visitors in

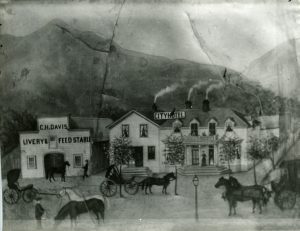

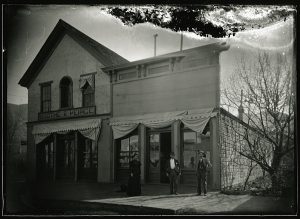

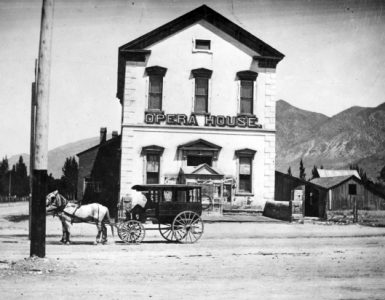

Starting with the first settlers, hospitality to travelers was important, whether they were visiting church officials, emigrant parties, or the growing numbers of freighters moving supplies to various locations. Local religious leaders were usually responsible for housing church visitors in  their homes, and there were no charges for bed and board or even feeding their teams. Bishops of wards were encouraged by Brigham Young to call suitable men to open hotels in their communities. When he was appointed bishop in 1855, Eli Harvey Peirce built a large adobe home on the east side of Main Street, just south of the public square where the courthouse was later erected. This became a hotel, and after Peirce’s death while serving a mission in 1858, was operated by Willis H. Boothe, who married Peirce’s widow Susannah. At first, the family lived in part of the building. After they moved into their own home those rooms and additional remodeling created the Boothe Hotel.

their homes, and there were no charges for bed and board or even feeding their teams. Bishops of wards were encouraged by Brigham Young to call suitable men to open hotels in their communities. When he was appointed bishop in 1855, Eli Harvey Peirce built a large adobe home on the east side of Main Street, just south of the public square where the courthouse was later erected. This became a hotel, and after Peirce’s death while serving a mission in 1858, was operated by Willis H. Boothe, who married Peirce’s widow Susannah. At first, the family lived in part of the building. After they moved into their own home those rooms and additional remodeling created the Boothe Hotel.

Other enterprising settlers followed suit. William P. “Cotton” Thomas built a two-story adobe house on Third North and Main in 1858. He not only operated a hotel, but also a livery stable well-suited to serving stage line travel. Mark A. Gilmore followed with a hotel at First South and Main, backed by feed stables and yards. After his call as bishop, Alvin Nichols kept an eating house at his home on the corner of First West and Forest. Samuel Smith and his wife Mary operated a hotel and she earned a reputation as an excellent English cook. Other eating houses were opened, independent of hotels.[Forsgren, 22-23 .Sarah Yates, “Downtown would amaze pioneers,” Box Elder Journal, (Brigham City: June 5, 1975), 2.[/mfn] As well as creating jobs and bringing cash into the community, the coming of the railroad was a boon to the hospitality industry. A Deseret News dispatch from Brigham City noted in 1868, “a considerable number of strangers are staying in our midst this winter. Mr. Rosenbaum’s hotel is overcrowded.”

Other enterprising settlers followed suit. William P. “Cotton” Thomas built a two-story adobe house on Third North and Main in 1858. He not only operated a hotel, but also a livery stable well-suited to serving stage line travel. Mark A. Gilmore followed with a hotel at First South and Main, backed by feed stables and yards. After his call as bishop, Alvin Nichols kept an eating house at his home on the corner of First West and Forest. Samuel Smith and his wife Mary operated a hotel and she earned a reputation as an excellent English cook. Other eating houses were opened, independent of hotels.[Forsgren, 22-23 .Sarah Yates, “Downtown would amaze pioneers,” Box Elder Journal, (Brigham City: June 5, 1975), 2.[/mfn] As well as creating jobs and bringing cash into the community, the coming of the railroad was a boon to the hospitality industry. A Deseret News dispatch from Brigham City noted in 1868, “a considerable number of strangers are staying in our midst this winter. Mr. Rosenbaum’s hotel is overcrowded.”

Communication with the outside world was vital, whether to keep in touch with the family back home or to conduct business, so settlers were excited when Brigham City’s first post office was established in July 1856 with Eli Harvey Peirce as postmaster.8Lydia Walker Forsgren, History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 20.

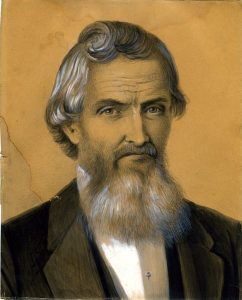

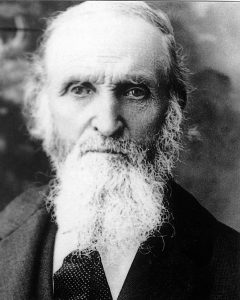

Brigham City’s first mail carrier, Owen “Blind Man” Jones, was unique. He emigrated from Wales to America in 1849 and to Utah in 1852, soon settling in Brigham City.

Communication with the outside world was vital, whether to keep in touch with the family back home or to conduct business, so settlers were excited when Brigham City’s first post office was established in July 1856 with Eli Harvey Peirce as postmaster.8Lydia Walker Forsgren, History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 20.

Brigham City’s first mail carrier, Owen “Blind Man” Jones, was unique. He emigrated from Wales to America in 1849 and to Utah in 1852, soon settling in Brigham City.

He was blind when he arrived in Brigham City, having lost the sight of one eye when a child, and the other when was working in a Welsh slate quarry. In spite of this handicap, he became well acquainted with the city, not only the streets but the exact location of homes.

For twenty-five years Mr. Jones carried the mail. The only assistance he received was to have the mail arranged in a certain order before he left the post office. Then with his knowledge of the city, which he had never seen, and his excellent memory he would deliver each letter to its proper destination. It is reported that Mr. Jones often acted as a guide to strangers in the city.9Forsgren, 267-269.

Notes

Search Brigham City Museum Collections

Add comment