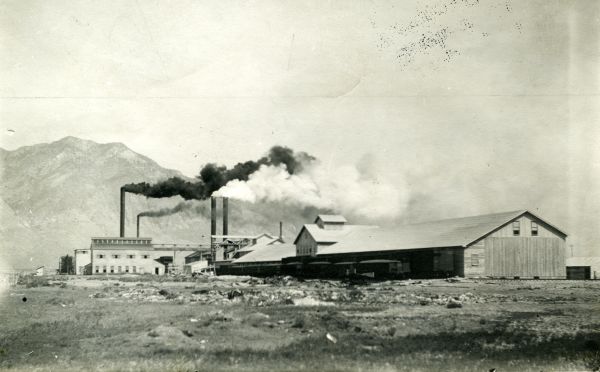

The city’s first major industrial project was not based on agriculture, but on the mineral properties of the “barrens” located five miles north and west of Brigham City. As early as 1893, H. C. Baker purchased large land tracts in that area, and set about trying to interest cement companies in development. It was 16 years later that two cement companies tested the deep marl beds, with favorable reports. In 1909, Chapin A. Day, treasurer of Marshall Field and Company Chicago, organized the Ogden Portland Cement Company and began construction of a cement production plant.1Lydia Walker Forsgren, ed., History of Box Elder County, (Brigham City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1937), 130. In the same year, the Oregon Short Line built a spur to the new cement plant.

All of this was promoted and followed closely by city officials, business leaders, local residents, and local newspapers, with the Box Elder News reporting on May 6, 1909:

In a few months, an industry will be in operation in this vicinity, which will involve the expenditure of hundreds of thousands of dollars, and yield profits almost untold…according to the promoters…

Mr. H. C. Baker of Ogden, owner of Lakeview Road, just north of Brigham City, will have a cement factory built on his property just west of his house for the purpose of manufacturing cement from the clay barrens which stretch for miles north and south….2“Big Cement Plant is now assured,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: May 6, 1909), 1.

The article went on to note that capitalist Chapin A. Day of Marshall Field of Chicago expected to have the factory “up and ready for operation and dedication this coming fall.”3Ibid., 1. In December, 1909, the newspaper reported:

True to the predictions of the officials of Ogden Portland Cement Company, the plan will be in operation by the first of the year. Indeed actual grinding will commence next week…

The company has erected three large buildings besides the boarding house and foundry. The boarding house is lighted by electricity furnished by the Brigham City power plant and heated with steam generated in the foundry.. It is the intention to enlarge the plant as time goes on, until there will be a small city of factory buildings.”4“Making Cement,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: December 23, 1909), 1.

At last the opening day arrived in January, 1910, as the Box Elder News reported:

Yesterday the clinkers began going through the burning kilns at the cement factory… In just a little time now, home produced cement will be offered for building purposes, and an industry will be in operation in our midst which will mean more than we can estimate, for the upbuilding of this community. Hail to the commercial cement, made from the old barrens.5Box Elder News, (Brigham City: January 6, 1910), 1.

Better employee access to the plant was needed, and the newspaper urged the Oregon Short Line to build a Forest Street motor line to avoid the “necessity of erecting more dwelling houses at the plant,” which they conjectured would bring in outside workers rather than jobs for locals.6Box Elder News, (Brigham City: July 20, 1911). A few concrete houses had already been erected close to the plant, and plans for “concrete farmhouses” were advertised in local newspapers, with Ogden Portland Cement used for their building. Local dealers included Merrell’s Lumber, Baker Lumber and J.B. McMaster and son.7Box Elder News, (Brigham City: December 14, 1911).

Better employee access to the plant was needed, and the newspaper urged the Oregon Short Line to build a Forest Street motor line to avoid the “necessity of erecting more dwelling houses at the plant,” which they conjectured would bring in outside workers rather than jobs for locals.6Box Elder News, (Brigham City: July 20, 1911). A few concrete houses had already been erected close to the plant, and plans for “concrete farmhouses” were advertised in local newspapers, with Ogden Portland Cement used for their building. Local dealers included Merrell’s Lumber, Baker Lumber and J.B. McMaster and son.7Box Elder News, (Brigham City: December 14, 1911).

It did not take long for the suggestion to take hold. An Oregon Short Line motor car leaving from Brigham City to the cement plant and returning in the morning and evening of each day went into service in April 1912, a “convenience much appreciated by the workmen even though it comes after the muddy season is over.”8“Motor Car Running to Cement Plant,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: April 4, 1912 ), 1.

There were unexpected benefits to the location of the cement plant, such as a 1913 Sports Carnival held on the newly-accessible barrens south of the plant. Enjoyed for decades after the plant closed was the “swimming hole” first described in August, 1913, by a reporter who “watched about 30 youngsters disporting themselves in the artificial lake made out near the cement plant by the excavation of marl and clay.” This long narrow strip of a pond or lake filled by water from the plant condenser and natural seepage was the “the blueist in color” of any lake in the area. “Some places are as deep as 20 feet, cold and invigorating with a slightly alkaline flavor, makes an ideal swimming hole….”9“The Old Swimming Hole,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: August 14, 1913).

For adults, the barrens provided the city’s first golf course, with a movement started in early 1914 by W. I. Hargis of the Baker Lumber Company. He mentioned it to Mr. Day of the Ogden Portland Cement Company, who “immediately proffered as much of the barrens as will be necessary.”10“Golf to become popular here,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: March 19, 1914). It was estimated that at least 100 acres would be needed to provide a seven-hole links. Hargis quickly signed up enough members at $2 each to put in the necessary improvements, and June 1914 saw the formal opening of the Brigham City golf links, on what had once been considered wastelands, but were now an asset.11Box Elder News, (Brigham City: June 25, 1914).

With potash a profitable by-product of cement, in 1918 the Ogden Portland Cement Company erected a modern potash factory with a spur track to supply the Baker Mine in the nearby mountains to the east, ending at Baker Siding near Call’s Fort. The plant was built to extract potash from the smoke produced in the production of cement. Although it was estimated that potash amounts would be small, it could be profitable due to the great value of the material used in manufacture of explosives and fertilizer. When completed, the potash plant would cover as much ground as the cement plant, excepting the stock houses. It was being constructed of cement and located immediately south of the east end of the cement plant so that smoke stacks were in line with the extractor.12“Potash Plant assuming form,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: July 5, 1918), 1.

Ups and downs in the local and national economy, as well as demands for building materials, affected plant operation, so there were often layoffs in the 1920s and early 1930s due to “a slump in building” or “sluggish market.” Industrial injuries were reported fairly often in the local newspapers, along with a couple of serious explosions caused by coal gas or “spontaneous combustion” of dust.

In 1922 the company provided “a fine new bus to haul the men.” The 22-passenger bus boasted a body made by Merrell Lumber, glass windows, canvas curtains, and was painted steel gray.13“New bus for cement workers,” ”Box Elder News”, (Brigham City: November 28, 1922), 1.

Even a new bus did not solve labor problems, with the plant shut down in March 1923 due to “disagreement between the company and men over the wage question.” At the time, the company employed 65 men.14“Cement Plant shut down,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: March 23, 1923), 1. It was never totally reliable employment, with the plant closed for repairs for nearly three months early in 1924, and then again in November, when it was reported that the plant “located at Baker Spur northeast of Brigham City” had laid off 40 men, with 20 still on the job, due to lack of market for cement.15“Central Plant practically closed down,” Box Elder News, (Brigham City: November 4, 1924).

With the Great Depression already nipping at its heels, the final blow to the Ogden Portland Cement Company plant at Baker Spur came on August 29, 1931, as fire struck the facility. According to the Box Elder Daily Journal of September 1, 1931, the fire was observed about 4 o’clock north of Brigham City by J. W. Howard of the Howard Cafe as he was driving north.16Box Elder Daily Journal, “Fire Destroys Warehouse at Cement Plant,” (Brigham City: September 1, 1931), 1. In what has been a point of controversy since that time, the Brigham City Fire Department was unable to respond to the call for help due to an insurance underwriters contract that forbade the city’s fire equipment to leave the city limits. Brigham City firemen responded by driving to the plant in automobiles, where they fought the flames as well as they were able, but fire spread through much of the plant. As can be imagined, this prompted a call for discussion of a combined city-county fire protection agreement. Investigation showed the fire had started through overheated electrical equipment, flashed through a warehouse full of 40,000 barrels of un-sacked cement, traveled the full length of the building, and also destroyed three boxcars on the siding.

Little attempt was made to rebuild the cement plant, and its closing forced closure of the potash facility, partly because the owners put their resources into operations in Ogden. It was a financial blow both to the Ogden Portland Cement Company and to Brigham City’s economy, as well to those who lost jobs in the beginning of a long slump in employment across the nation.

The cement plant and adjacent potash facility gradually deteriorated, largely unnoticed until Interstate Highway 15 was being built, and an attempt was made to raze them. Their remains, especially those of the cement and steel rebar potash plant, proved stronger than the blasts used to destroy them. The skeletal remains of the Ogden Portland Cement Company plant still stand adjacent to Interstate Highway 15, providing an easel for ever-changing colorful graffiti.

Add comment